The African Swine Fever epidemic spread across in much of Europe, and has affected both wild boar and domestic pigs. This disease is one of the most complex and most important of those affecting pigs whose presence has important socio-economic repercussions for the countries that suffer from it. That is why, EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) was asked to continue and improve the risk assessment activity. For this, information on the density and distribution of the wild boar is important.

How can we help? From iMammalia we encourage you to collaborate actively. It is simple, through the iMammalia mobile application you can record any sighting or trak of wild boar (and other wildlife), also providing information about the location and, if possible, a photo of the trail or animal.

In addition, soon from the iMammalia application, when formalizing a record of sighting of a dead wild boar, a notice will be automatically sent to the corresponding authorities depending on the location. They will be in charge of transporting it so that a center, veterinarian or similar, specialized in epidemiology, can verify if it is positive for ASF or any other disease.

But, how can we identify a trail of wild Boar? In this post we give you the necessary information so that you become an expert in the tracking of this animal.

Wild Boar prints in the environment different traces after feeding, comfort or intraspecific communication activities which allow us to easily identify their presence in the place. Among them, the most common are the following:

Tracks

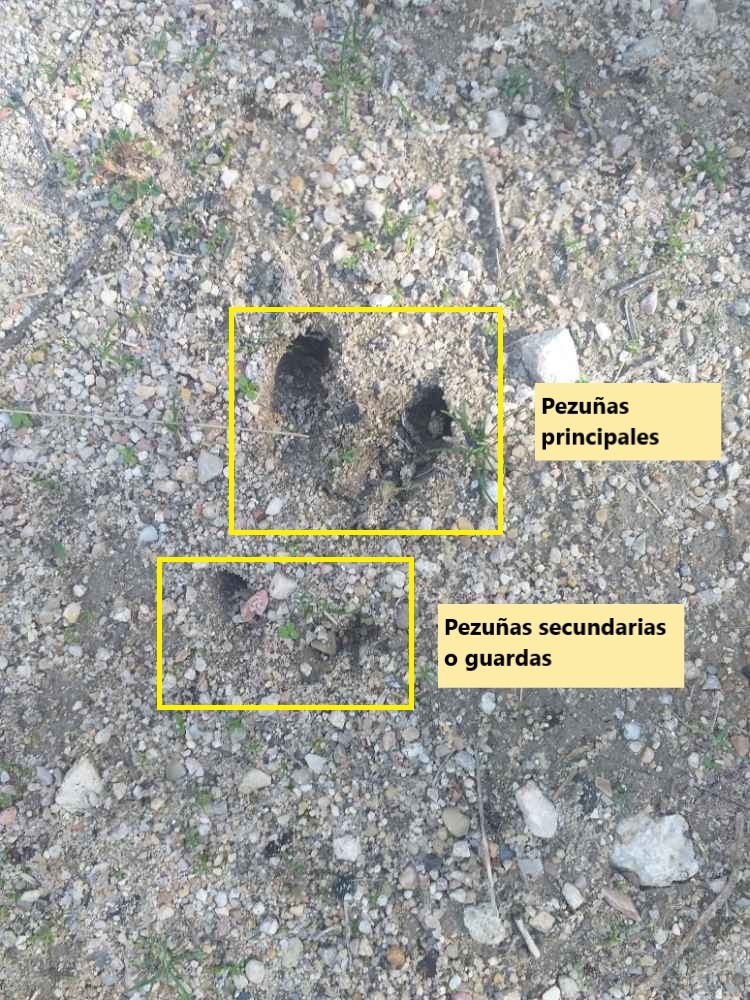

A wild boar, unlike another ungulate, marks the four hooves, the two main and the two secondary or guards (Fig 1), although this does not always happen. On the other hand, the marks of the secondary hooves, in wild boar, stand out from the primary ones something that does not happen when the rest of the ungulates mark them.

Figure 1. Tracks of a wild boar’ s hooves. Marked the main and secondary hoof. Photo by Pablo Palencia

Figure 2. Wild board’s tracks. Foto by Pablo Palencia

Figure 3. Red deer’s tracks. Photo by Javier Fernández

Another difference that facilitates its identification is that, in the case of wild boar, the tip of the hooves is rounded and the track is shaped like a trapezoid. (Fig 2) whereas, those of other ungulates such as deer is rectangular (Fig 3)

Figure 4. Young wild boar’s tracks. Photo by Marek Bebłot

By observing the prints, we can identify if they belong to a young or adult individual. In young individuals the imprints of the secondary hooves can be very weak or non-existent, although in the vicinity they are usually found traces of adults. In addition, as they advance in age the tips are rounded, being only pointed in young individuals. Hoof pads are usually not marked (Fig 4 and 5).

Figure 5. Adult wild boar’s tracks. Photo by Javier Ferreres

Prints measurements vary depending on age and sex. The average width of a print (not counting the secondary hooves) is about 6 cm, and the length is between 6.5 and 7 cm, reaching 10-12 cm if we add the secondary ones. The marks of fingers 3 and 4 (main hoof) are usually symmetrical. The mark of the front prints is deeper and more marked, due to the distribution of the weight of the wild boar’s body on the front. On the other hand, depending on the opening of hooves we can know if the animal was jogging or passing (slightly open), or at a higher speed (divergence of V-shaped hooves).

Bathtubs

These are areas where wild boars come to bathe and impregnate their fur with mud to eliminate parasites and prevent their appearance. These bathtubs are located anywhere with the presence of mud such as small ponds, banks of streams or lagoons, forest tracks … (Fig 6 and 7).

In these baths the body of the animal is marked, with an oval shape and the fur which resembles “brushstrokes” in the mud. Near them it is common to find scrapers on the trunks of trees.

Figure 6. Wild board’s bathtubs. Photo by Javier Ferreres

Figure 7. Wild board’s bathtubs. Photo by Aleksandar Miletic

Rubbing marks and other traces

In the trees we can find two types of signs:

Normally, when the wild boar wallows in the bath, it goes to the trees and shrubs to rub itself. This causes the trunks of the trees to be left with a layer of mud and smooth bark, these marks match the height of the animal. (Fig. 8 and 9).

Figure 8. Rubbing marks of wild boar against a tree after bathing in mud. Photo by Saúl Jiménez

Figure 9. Rubbing marks of wild boar against a tree after bathing in mud. Photo by Joaquín Vicente

Wild boar hairs

Wild boar hairs are characterized by being black or grey, long, very hard, open and broken at their end (FiG 10). These hairs frequently appear on barbed wire or fences. It is also very common to find them in the bark of trees where they are scratched (Fig11), in baths, in their resting sites etcE

Figure 10. Wild boar hairs. Photo by Javier Fernández-López

Figure 11. jabali hairs on a tree trunk used as a scraper. Photo by Pablo Palencia

Feeding marks

They are created when the wild boar removes the earth with the jeta in order to extract food such as insect larvae, roots, bulbs … (Fig 12) Its appearance resembles a carved floor, normally these areas of removed soil are aligned and become wide and bifurcan in all directions. In the fresh meadows you can see raised areas, with remains of grass and earth surrounding the sickle (Fig 13). Its extension is variable and can constitute small extensions near ponds, streams, along forest tracks … or larger areas in fresh meadows, undergrowth etc. In addition, the wild boar, in its search for food, also moves large stones (Fig 14).

Figure 12. Wild boar root in the earth. Photo by Niedziela Katarzyna

Figure 13. Tracks of rooting by wild boar. Photo by Javier Ferreres

Figure 14. flipped stones. Photo by Joaquín Vicente

The ‘’masquejones’’ or ‘’mascadas’’ are balls of vegetable remains that the wild boar discards after chewing the leaves of some grasses, such as esparto grass or albardine (Fig 15). This behavior does it when it feeds on unusable plants in order to get the most juice possible.

Figura 15. Masquejones of wild boar. Photo by Jose Antonio Blanco.

Lairs, resting sites

Wild boars do not usually exert themselves in the elaboration of a lairs, except for those used in childbirth (large balls of vegetable mass made with branches and leaves, to protect the young during the first days of life), they simply lie in the place that gives them tranquility and protection such as thickets, reeds etc. so small depressions or scratches of the ground are appreciated. To know if that depression is a wild boar lair we can look, for example, at the presence of thick hairs. Lairs can be added if used by females with offspring.

Figure 16. Lair of wild boar. Photo by Aleksandar Miletic

Faeces

Wild boars deposit their droppings anywhere. Its feces have an elongated shape and are constituted in turn by units that imitate the shape of a beret which do not similar to other ungulates feces. (Fig 17). They are usually about 3-5 cm wide. When they are fresh they have black and shiny color; when dried they disintegrate and appear loose (Fig 18). the content of the feces is mostly vegetable, although remains of insects, hair etc. may appear.

Figure 17. Droppings

of wild boar. Photo by Azahara Gómez

Figure 18. Droppings of wild

boar. Photo by Javier Ferreres

Paths in crops

Figure 19. Maize cultivation path marked by the presence of wild boar. Photo by Fabio Carnaroglio

In corn, sunflower and cereal crops it is possible to find very marked paths with damaged plants, accompanied by chewed grain, hooves and wild boar droppings (Fig 19).

Carcasses and bones

It is common to find a wild boar carcass, either without cause that we can identify in situ or by running over, hunting or predation (Fig 20 y 21). The animal is easily identifiable depending on the state of decomposition in which it is.

Figure 20. Carcasse of wild boar. Photo by Laia Casades Marti

Figure 21. Wild boar run over. Photooto by Rafał Dubełe

When it is only bones that we find, the wild boar skull can be identified by its elongated shape and its hard, curved and highly developed canines (Fig 21 and 22)

Figure 22. Wild boar skull. Photo by Paweł Kobyłecki

Figure 23. Lower jaw of wild boar. Photo by Joanna Gornia

In the case of finding a wild boar carcass it is important not to touch it, as it can be a carrier of a disease such as African Swine Fever (ASF), and immediately inform and report its location to the rural agents of the corresponding autonomous community.